23rd March 2025

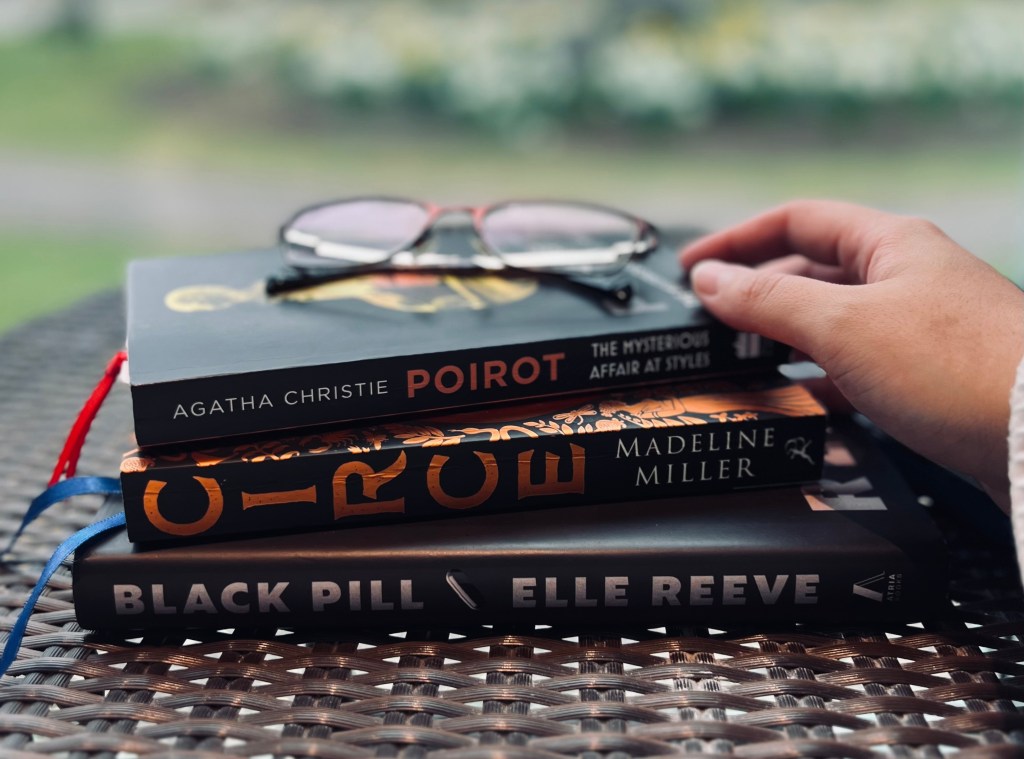

On this grey and drizzly Sunday I have taken refuge in my local spa, a brief weights session, a dip in the pool, and a book to finish just about distracted me from the gloomy outdoors. This week we travel to Ancient Greece to trace the story of an exiled goddess; to Essex where we join Hastings and Poirot on their inaugural case; and finally, for a break from the fiction, to a decade ago in America where a Vice journalist unravels the passage of events that led to the 2017 Charlottesville tragedy. I hope you enjoy this week’s reading.

Circe, by Madeline Miller

I picked up Circe on a whim a few months ago, drawn in by the setting of Ancient Greek gods, and finally tempted by the flattering reviews on the front cover – and though one should never judge a book by the latter, the ornate bronze and black cover was pleasing to the eye. Greek mythology has always fascinated me. The mainstream religious texts portray their deities as paragons of virtue, and rarely acknowledge the hypocrisy contained within the pages, Greek mythology is much less forgiving. The gods are of course, omnipotent, omnipresent, omniscient, but they are also jealous, bitter, resentful, merciless. Humanity manifest. Showing a deep contempt for mortals, especially among the most powerful gods, they see humans as nothing more than flies, fleeting lives that will disappear in an instant. They hold themselves superior in every way, and yet they squabble, deceive, slaughter, much in the same way as the creatures they see as no more valuable than dirt. The only difference is they can’t die, so they can go on feuding and hating and pillaging for millennia – okay, they have some pretty awesome powers too. I could continue for pages about Greek Mythology – perhaps that is another post – but this lays the groundwork well for understanding the themes explored in Madeline Miller’s Circe, the retelling of a classic mythology.

Circe, daughter of Helios, god of the sun, and Perse, an Oceanid nymph, is born a disappointment to her parents, with a mortal voice and no significant destiny. Her fleeting childhood, for gods grew quickly, was marred by rejection from her family. Her mother had been disappointed she was not fated to marry a great god, and discarded her in favour of trying for another child. Her siblings Pasiphae and Perses, spent most of their days tormenting Circe in their father’s great halls, disparaging her looks, voice and demeanour with vile and repulsive taunts. Her father cared not for his children, until they became a problem, or a means to an end. So, Circe spent her first few hundred years in misery, resigning herself to a life among gods and nymphs who, while malevolent toward one another, seemed to unite in torment of her. It is an exaggerated parallel that I’m sure many of us can relate to on a mortal degree, not fitting into society’s cookie cutters is a lonely existence and it is not difficult to feel Circe’s pain – though some small grace is not having to face it forever.

Circe realises her destiny when the flowers she enchants transform her mortal love into a powerful god of the sea, but her gift comes at a price. Her artistry in witchcraft threatens Olympus and in penance for her defiance against the gods she is exiled to the island of Aiaia. There she builds her sanctuary, practicing and refining her art, taming wild beasts and growing herbs in a well-tended garden. Not before long visitors begin to arrive, some bring friendship, some bring terror, and one brings destiny; Odysseus, Greek hero of the Trojan war, favoured mortal of the goddess Athena. Circe is a story of family, love, and tragedy, and ultimately of discovery. Circe, a lesser goddess trying to dazzle in a world of unparalleled nymph beauty and hideous god power, discovering her limits and how to exceed them.

A Homer for the modern age, Miller beautifully retells the tragedy of Circe in an adaption fit for the modern age, yet retaining the majesty of the original mythology. I highly recommend this book to any keen reader or lover of Greek mythology.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles, by Agatha Christie

I first fell in love with Monsieur Poirot, and by extension the works of Agatha Christie, when curled up on my Grandma’s sofa we would watch the ITV adaptation of the famous detective, played expertly by David Suchet. Reading the books takes me back to those times, the tattered sofa in garish floral tribute, with covers hiding worn arms in equally dated textiles – for all the love I have for my Grandma she had interesting tastes in interior design. The house was always heavy with the scent of living; pets, books, soap, it was the quintessential loved family home. It is shocking then, that having been a fan of Poirot and Christie for so many years – for those sofa days are further back than I care to calculate – that I have never gone to the origin, to the novel that started M. Poirot on his journey to becoming one of the most famous fictional detectives in history.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles was not Christie’s first literary attempt, but it was her first detective story, born of a dare from her sister, Madge, who “bet you can’t write a good detective story”. Inspired by the Belgian refugees arriving in her hometown of Torquay, and her job in the local hospital dispensary, Christie devised her detective and her murder. Persisting through a number of refusals to publish, Christie eventually found a publisher willing to work with her, and her first book went on sale on 21st January 1921. Reviews of the book were favourable, and despite Christie’s initial insistence that she would not pursue a writing career, and luckily for the rest of us, The Mysterious Affair at Styles set in motion the dawn of a prosperous career for Christie.

Having read a number of Poirot novels by now, I wasn’t sure what to expect when I journeyed back to the beginning. Are books like pancakes, does the first one turn out a little bit wonky before you perfect your technique? Besides perhaps a slight repetition I have not noted in her subsequent works, The Mysterious Affair at Styles embodies all the thrilling misdirection that is the crux of Christie’s work. The path through suspicions, motivations, and little evidence, to the murderer is a turbulent ride with a number of cleverly placed veers in suspicion. I have to admit I let out an incredulous chuckle when Monsieur Poirot revealed the identity of the killer, feeling some of the shock that poor Hastings must have felt, and perhaps some of the foolishness that I was so far wrong yet again. And yet, time after time it is a delight to be bested by one of the best literary minds in humanity.

With well-written characters and carefully timed intrigue, The Mysterious Affair at Styles is thoroughly enjoyable, ingenious, and hard to put down.

Black Pill, by Elle Reeve

How I Witnessed the Darkest Corners of the Internet Come to Life, Poison Society, and Capture American Politics.

Black Pill is a stark journalistic view from the trenches of the incel and alt-right communities that laid the foundations for the 2017 Charlottesville terrorist attack, resulting in the tragic death of Heather Heyer.

In Black Pill, Elle Reeve recounts her exploration of the events that led to the Charlottesville ‘Unite the Right’ rally, subsequent riot, and tragic death of an innocent woman. From a proto-incel community on 4chan a seed of hate blossomed into a subculture where self-proclaimed ‘involuntary celibates’ developed the belief that their lack of sexual gratification was the fault of women. This manifested over time, in the sordid, anonymous, corners of the internet, into a passionate and violent philosophy. These men were owed what they were being denied. Rape and assault were celebrated as the just response to the injustice being compelled upon them. The danger of this philosophy was realised when it crept out of the internet and into the real world; when mass murders were committed by members of the subculture who had been taken in by the misogynistic, self-pitying, entitled ethos of the community. The name of Reeve’s book draws its inspiration from a belief held, most commonly, by incels; that women are shallow creatures who choose only the most handsome, society-approved, men, the ‘Chads’. To be ‘blackpilled’ is to believe that society is broken, geared only towards the ‘perfect people’, that your place in the system is anchored, hopeless. Takers of the black pill believe they have been dealt an unlovable hand in life, that nothing they can change (personality, looks or otherwise) will ever help them achieve their romantic and sexual dreams.

It was when this community collided with another, a Nazi movement growing in confidence, that the extremism reached new heights. Fred Brennan had developed 8chan as a place for free speech, that is another thread unpicked in Black Pill, but it was eventually infiltrated by a growing alt-right movement that expelled users with neutral, or at least more neutral ideals than their own. It became the birthplace of QAnon, where conspiracies and absurdities were woven into truth and ultimately stormed the Capitol in 2021, in one of the worst attacks on democracy America has seen in recent years.

Reeve is brave, not afraid to put herself in danger so that the world may know not only of injustice, but of the events that lead to it. Resilient and resolute in interviews that would have had most of us seething in anger. Her ability to remain outwardly unbiased in interviews to gain the trust of her subject, is an art. She knows how to lay her words carefully to unravel the darkest motivations of the interviewee, pressing them just enough to reveal themselves, but not so much that they build a wall. She sees that behind the faces of “evil” are complex emotions, motivations, tragedies, and ignorance. Understanding the steps in the path to Charlottesville; rising confidence in racists, a lonely man lamenting his disability, ignorant views on eugenics, and the rise of social media that gives platform for all the latter to be turned over in anonymity, is a stepping stone on the path to understanding extremism. We can condemn racists, bigots, misogynists, but without being willing to understand the root of their beliefs, we cannot hope to combat, or educate, it.

One question that Reeve explores, that I played over and over in my mind on closing the book, and continues to fascinate me, is the question ‘are fascists stupid?’ Most people would probably say “Yes. No argument, they are stupid, they are idiots”. I see it repeatedly when Trump or Musk raise their moronic heads in conversation or on social media, and there are clamours of ‘he is so stupid’, ‘he doesn’t know what he is doing’. Whilst many of the decisions we see being made in the Oval Office are beyond the comprehension of any sane person, the fact is they are occupying the Oval Office. These two ignorant, bigoted men occupy the highest office of one of the Western power houses. The decisions they make are stupid, their beliefs are stupid, but are they? Whilst I don’t disagree with the general sentiment that fascists are stupid, Reeve raises an important point, by dismissing people as stupid or idiotic, you underestimate them, you think they cannot possibly achieve what good, intelligent people can achieve, and yet history has proven this to be a flawed philosophy time and time again. There have been many awful, but awfully intelligent people, so why are we so resistant to the fact that intelligent people can be evil? Reeve puts it eloquently in her book:

“Smart people have been told all their lives that being smart is a virtue, and, implicitly, smart people are virtuous…the sick, sad truth is that the world is not being ruined by dumb monsters but by smart people just like us.”

The Nazi’s who feature in Reeve’s interviews can be eloquent, even politically astute, as Reeve puts it, “they notice that smart people need to feel like they’re logical, principled thinkers, so they create cringe propaganda to make them feel alienated from activists for social justice.” Those are not the actions of the stupid, but of intelligent, if thoroughly misguided, people. I must say at this juncture that I do believe the atrocious, tangled web of entitled eugenic misogyny at the heart of the incel and Nazi belief systems is unquestionably stupid. But the people who lap it up, lap it up for a reason, and if we want to educate against fascism and extremism we must lower our own prejudices and understand the root cause. Extremism can be a learned behaviour, it can be based in faith, or a response to legitimate dilemmas. Confused, alienated, frustrated, people come together with a shared goal and leave with a shared ideology, often targeted at something besides the root cause of their unhappiness, for it is far easier to imagine an enemy than to self-reflect.

I could go on, but I do not want to detract from Reeve’s work. An important piece of journalism for the modern age Black Pill lays bare the power of the meme, of social media, and of combined discontentment and ignorance.

I hope you have enjoyed this week’s reading, I would love to hear what you have read this week.

Happy Reading!